Octavia Butler’s Science Fiction Predicted the World We Live In

Mural with a portrait of Octavia Butler and her name, composed of dots of various densities in 3-D space. All of the artwork in this story is in this style. Four students stand in front, gazing at her portrait. The point of view moves from the opposite side of the wall, through the mural, before moving behind the students as the dots fade away.

Sixteen years after her death, the writer Octavia Butler is experiencing a renaissance.

Butler, seen here on a mural at a middle school that bears her name, is celebrated for novels that grappled with extremism, racial justice and the climate crisis.

The future she wrote about is now our present moment. What follows is a tour of the worlds that made her — and the worlds that she made.

She wrote 12 novels and won each of science fiction’s highest honors. In 1995, she became the first science fiction writer to be awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant. The MacArthur Foundation said of Octavia E. Butler, “Her imaginative stories are transcendent fables, which have as much to do with the future as with the present and the past.”

Part of what has made Butler so beloved is the work that preceded these honors: the way she envisioned her own future and encouraged herself to keep going despite the very real obstacles in her path. She recorded her goals and aspirations in her personal journals in terms that have since resonated across the decades:

I will buy a beautiful home in an excellent neighborhood.

I will help poor Black youngsters broaden their horizons.

I will travel whenever and wherever in the world that I choose.

My books will be read by millions of people!

So be it! See to it!

With great discipline, she engaged honestly with a set of questions about who she was and where she was going. Her responses were intended for her publisher — and ultimately for the world — but they were written especially for herself.

While drafting one autobiographical note, she described herself as “a hermit in the middle of Los Angeles — a pessimist if I’m not careful, a feminist, always a Black, a quiet egoist, a former Baptist and an oil-and-water combination of ambition, laziness, insecurity, certainty and drive.”

She is also, increasingly, a writer recognized as one of the most important voices and visionaries of the 20th century, and now the 21st.

Since her death at 58 in 2006, after a fall outside her home in Lake Forest Park, Wash., her novels have inspired art installations, librettos and jazz suites. They now appear on university syllabuses and high school reading lists. Her extensive archives, housed primarily at the Huntington Library in San Marino, Calif., contain her voluminous notebooks and meticulous research. She led the way for the next generation of Black readers, thinkers and builders to picture themselves in the collective future, laying the groundwork for an Afrofuturist movement before the term even existed.

Five adaptations of her fiction are currently in various stages of film and television development, by producers ranging from J.J. Abrams and Issa Rae to Ava DuVernay. “Kindred,” her now canonical 1979 novel about a Black woman who is yanked back in time to the antebellum South and marooned on a working plantation, will premiere as a TV series from FX in December, adapted by the playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins.

In 2020, in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, many readers turned to Butler’s 1993 novel “Parable of the Sower,” which details the journey of a visionary and headstrong teenager, Lauren Olamina, set against a California landscape besieged by climate change and socio-economic crises — so many readers, in fact, that the novel appeared on the New York Times best-seller list, a first for Butler, fulfilling her stated lifelong dream 14 years after her death.

As a Black woman and a writer, Butler demolished walls that seemed impermeable, writing on themes that seemed uncategorizable.

This year marks the 75th anniversary of Butler’s birth. Her themes, ideas and characters continue to resonate with new readers at a time when so many are looking for, if not hope, then a map for a way forward.

What readers, fans and scholars often note about Butler’s work is its predictive qualities: Her vision about the climate crisis, political and societal upheaval and the brutality and consequences of power hierarchies seems both sobering and prescient.

But, as Butler often noted, being right was never the point. She didn’t want to be right — far from it.

She wanted to give us time, and tools, to correct the course.

The Beginning

1947–1959

The World That Made Her

The

World That Made Her

The point of view pans out from the side of the Los Angeles Central Library, before turning to reveal the front facade. As the viewpoint zooms out, points come into focus as trees. The viewpoint pulls out to show foliage and trees along with a blue tiled sign of Los Angeles Public Library.

As a young woman living in Pasadena, Octavia Butler often took the long bus ride into the busy maze of downtown Los Angeles to visit the multistory Central Library.

“I’m a writer at least partly because I had access to public libraries,” she later reflected.

“I am also a product of librarians who read stories to groups of avid little kids.”

Octavia Estelle Butler was the daughter of a shoeshine man, who died when she was a baby, and a maid. A self-described loner, Butler always stood apart: far from the loud tangle of children at recess, standing in the shade of the generous sycamore and oak trees of Pasadena or secreted inside her bedroom in the after-school hours, lost within some exotic elsewhere of storybooks.

Some of the books were her own, saved up for, while others were hand-me-down castoffs rescued by her mother, who scrubbed, dusted and ironed in houses in the majority white and wealthy Pasadena neighborhoods that were adjacent, yet worlds apart, from her own. Butler’s mother walked her to the library, where they signed up for a card. That small slip of paper became her passport to travel widely.

Boundlessly curious and a keen observer, Butler lived vividly in her imagination. The stories between the covers of those books served as a balm, providing locales within which she could disappear, occupy new settings, explore new possibilities and try on new characteristics. She began making up stories at 5 or 6 and regaling her mother with them.

She read with thirst and purpose. She became a fixture at the Peter Pan Room, the children’s section of the elegant Pasadena Central Library. When she’d exhausted those shelves, she was dismayed to learn that the adult stacks were off limits until her 14th birthday.

She developed workarounds. She saved up change, which sang in her pocket as she walked to the store to purchase her first books — about horses, dinosaurs and the stars she could barely see because of the scrim of Southern California smog.

“Here I was trying to write about Mars,” she recalled as an adult, “and I knew nothing about it.”

The point of view pans through a work space, illuminated by four standing lamps. In the back are rows and rows of bookshelves. As the viewpoint moves forward through the space, the details of the green rug on the floor and spines of books become more visible. Once the viewpoint reaches the bookshelves, it turns right into one of the corridors, before the bookshelves dissolve and fade to black.

Libraries, with their grand stacks and hidden carrels, were more than a safe space for Butler: They provided possibilities.

Sitting in the hushed cocoon of the library gave shape and structure to her days. It gave her a role. It gave her purpose.

Whenever Butler felt dispirited — about not having a mentor or a steady income or a clear path forward — she’d remind herself that she always had two things: her desire and access to aisle upon aisle of books.

At school, Butler struggled to find her footing, but the sciences captivated her. They hinted at something larger — a series of open questions.

“I liked science documentaries, whether they were television movies or the kinds of films that teachers showed at school,” she once said. She recalled that moment when the world fell away, after the teachers rolled in the AV equipment, the lights dimmed and the projector started to whir.

“I got my first notions of astronomy and geology from those little films,” she said.

These visions transported her far away from Pasadena and the hemmed-in feeling she often fought.

At the edge of the Angeles National Forest, she could see NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a cutting-edge institution that attracted scientists from all over the world. But her Pasadena — the segregated city of her childhood — seemed to occupy an entirely different universe.

Her imagination, she knew, was a means to escape this cul-de-sac of despair.

But she needed a plan.

The point of view moves through the front windshield of a bus, passing rows of seats inside, before reaching the back of the bus, where the San Gabriel mountains are visible through the back window. Then the bus dissolves and fades to black.

For Butler, the bus in Pasadena was a necessary link from here to there. Sitting high above the cars, she could take in the shifting landscapes: It gave her a window into different worlds.

On the bus, she might find herself drawn into a conversation, or eavesdropping on an exchange that would ignite a new idea.

She’d flip open a notebook, careful to catch a stray idea, if only a seed of a seed — afraid that it might slip away.

“Los Angeles is so spread out that almost any bus ride will be a long one,” Butler once observed. “The time proved perfect for writing.” Her bus rides also allowed her to make sketches of potential characters. “I especially collect people — those who stand out in some way,” she said.

In Pasadena, Butler was surrounded by hills and mountains, and she’d watch them change from green to brown. The magnolia and pomegranate trees grew heavy with blooms or fruit, and she carried pocket-size memo pads to record their growth, from year-to-year — gauging how well, or poorly, the trees were doing. She saw how important it was to nurture the natural world. This too was part of a larger story she was investigating, about the changing earth.

At her mother’s urging, she wrote her stories down — on stray sheets of scrap paper, on waste bin letterhead or in her dime store notebooks.

In an act that was viewed as wildly indulgent by her extended family, Octavia Margaret, Butler’s mother, presented her daughter, Estelle (as her family called her), with a typewriter for her 11th birthday: a heavy, manual behemoth that she had no clue how to operate. But it was a powerful talisman — a symbol of seriousness. She hunted and pecked a path forward.

Late one night, Butler happened to tune into a broadcast of a campy, science fiction B movie titled “Devil Girl From Mars.”

At 12 years old, sitting in the blue glow of the family’s new television, she thought the film was a revelation: It was spectacularly bad.

Someone got paid to write this, she thought. Imagine that.

The Breakthrough

1978–1979

Where ‘Kindred’ Came From

Where ‘Kindred’ Came From

At her writing table, focused on the future, the adult Butler often questioned and re-questioned: Are we ever free of our past? Not just of our personal choices — the boons or blunders — but of the uncomfortable histories we inherit, and the ways in which we are inexorably tied to them?

She had long since left behind the fantasy stories and horse romances she wrote as a girl to turn her attention to science fiction — to the forms and shapes of the stories she had read in magazines such as Amazing Stories, Fantastic and Galaxy Science Fiction. Here, she would find her voice, her way, her purpose.

The blank page now had depth for her. Writing felt like leaping into vast, deep water. Without limits, where might she travel?

Having published several novels and built a small following, Butler used the meager, hard-won funds she’d earned from the sale of her most recent book, 1978’s “Survivor,” to embark on her first research trip. She traveled by Trailways and Greyhound buses to Maryland for library research and to take in the physical world of a plantation.

During her trip, she was struck by the erasure she witnessed on a visit to George and Martha Washington’s Mount Vernon home, where tour guides never referred to “slaves,” instead calling them “servants.”

Butler later wrote that her research made the book that came out of this trip one of the most difficult for her to live with, as she absorbed the losses, the grief and the slave-narrative voices of the dead.

The finished novel became one of her best-known books: the genre-defying 1979 classic “Kindred.”

In “Kindred,” the main character, Edana “Dana” Franklin, is a struggling Black writer who is setting up her new house with her white husband, Kevin, when she unexpectedly travels through a mysterious seam in time from her life in contemporary Southern California to a working plantation in the antebellum South. Throughout the novel, she is whipsawed back and forth between the two eras, dropped repeatedly into a violent landscape that she comes to understand is not simply occupied by her forebears but is, in fact, her inheritance.

Butler always described “Kindred” not as science fiction but as a “grim fantasy.” It doesn’t contain the genre’s typical trappings or devices; there is no time machine, no hard science. In a clear, creative sense, Butler saw history itself as an otherworldly landscape to be explored: foreign yet familiar.

“‘Kindred’ was a story of ordinary people trapped in fantastic circumstances,” Butler wrote in a 1988 notebook. The antebellum South was “like another planet to Dana and Kevin — people of ‘now.’”

“There is no book like it,” said Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, the playwright and screenwriter who is adapting “Kindred” for FX. “When I revisited ‘Kindred’ in 2010, the book cracked open for me in a different way than it did when I first read it,” he recalled. “People forget this book is 45 years old. People forget this is literally a half-century-old book.” But, he marveled, “it’s still immediate.”

Cotton plants in a cotton field. The arms of two figures appear, with one hand gripping the hand of the other figure. They loom large among the environment, almost architecturally. As the point of view passes through the arms, the lone arm left in the frame dissolves before the rest of the cotton field fades away.

While researching “Kindred,” Butler toured the cotton fields of Maryland to shape her vision of how the past reaches out to the present, and how the histories of Black and white America interact.

“In this country,” Butler jotted in some stray notes while writing the novel, “whether we like it or not, Blacks and whites are kindred.”

“Kindred” remains a portal, the doorway through which many readers — science fiction enthusiasts and beyond — first encounter Butler. However, the book also assertively advanced a larger discussion about the untended wound of slavery and how it shapes our present-day environment — our ability to create connections, to find community — in a way that hadn’t been attempted in fiction before.

The novel endures in part because the bracing candor and brutal immediacy of the story meet contemporary readers where they are, said Ayana A.H. Jamieson, the founder of the Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network, a global community dedicated to Butler’s work. “Kindred” encourages readers to grapple with hard questions about kinship and alliances, and about what it means to survive.

“Part of the underlying message of this book,” said Jamieson, “is while this is one person dealing with their own family history, it is also all of us.”

Premonitions

1993–2006

A ‘Parable’ Foretold

A ‘Parable’ Foretold

“I began writing about power because I had so little,” Butler repeatedly asserted in her journals, in interviews and in conversations about her life as a writer. She was curious about how power worked, how it changed from hands to hands, always asking: What might her characters do with power? What might power grant them?

She gave characters in her stories — often wily, adaptable women — the power and ability to fight using whatever means, modest contrivances or hidden superpowers they had.

She also threw plenty of trouble at them to see how they might survive.

This exercise in creativity closely mirrors Butler’s own experience in life. What Butler’s heroines have in common is the resourcefulness and grit to make something of nothing — the ability to problem-solve, time and time again.

This same spirit animates the way in which many read Butler now: not just as a gifted storyteller but as someone who saw, in the distance, the crises we’re now struggling to overcome.

One novel that seems especially prescient is 1993’s “Parable of the Sower.”

Like Dana in “Kindred,” whose time-slipping irrevocably alters her present, Lauren Oya Olamina, the main character in “Parable of the Sower,” watches, aghast, as all that she has known vanishes: her family members, her community, her comforts and her way of life.

Like Dana, Lauren is thrust into a life-or-death predicament that she must puzzle out to survive. But her tangle is not a contest with the past. Rather, it requires confronting a deeply uncertain future.

Lauren, who is 15 at the novel’s outset, lives in the fictional Southern California town of Robledo, a gated community 20 miles east of Los Angeles’s glowing sprawl. Her hometown is in ruin, a war zone. Earth, as its residents have all known it, is descending into disaster — never-ending drought, social upheaval and violent class wars.

Lauren begins keeping a journal in which she fashions verses that will become the foundation of a new faith: Earthseed, which embraces the inevitability of the change that continues to buffet, disrupt and radically reform her life.

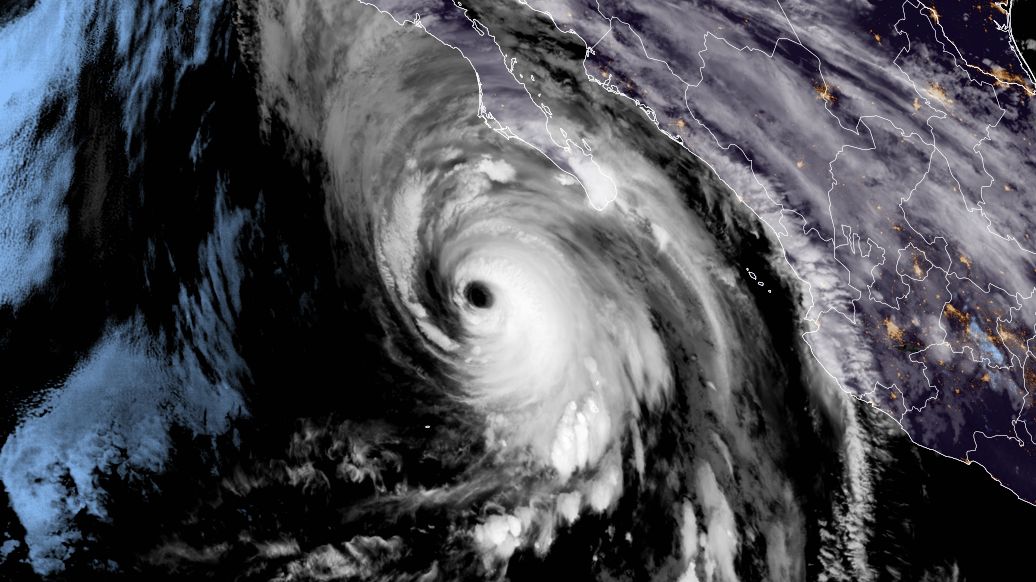

A cloud of orange-red smoke, before the point of view pulls back through a barren landscape of trees on fire. Dark red clouds emerge in the distance, and individual dots that comprise the trees and the greenery are illuminated, almost like sparks.

In “Parable of the Sower,” Earth is tipping toward climate disaster: A catastrophic drought has led to social upheaval and violent class wars.

Butler, a fervent environmentalist, researched the novel by clipping articles, taking notes and monitoring rain and growth in her Southern California neighborhood.

She couldn’t help but wonder, she later wrote, what “environmental and economic stupidities” might lead to.

She often called herself a pessimist, but threaded into the bleak landscape of her “Parable” novels are strands of glimmering hope — ribbons of blue at the edges of the fictional fiery skies.

“There are some of us who read the ‘Parable of the Sower’ (and its sequel the ‘Parable of the Talents’) as sacred text,” the author and activist adrienne maree brown, who uses all lowercase letters in her name, wrote on her website. Along with the musician Toshi Reagon, brown began hosting a podcast, “Octavia’s Parables,” during the earliest months of the pandemic. “Everything she wrote is provocative and interesting, but in the ‘Parables’ she cuts in right next to her own story, and many of ours, a Black girl creator, surviving,” brown wrote.

Butler saw these threads in her own work. “I seem to be saying something without trying,” she wrote. “That Black women are survivors, that they have to be strong because so much is demanded of them,” something that “both my mother and my grandmother discovered firsthand.”

In “Parable of the Sower,” as Lauren ventures out into the world to find a new home, she collects a daisy chain of fellow travelers. Together they make their way toward freedom in a new settlement they christen Acorn.

Lauren understands that Earth is suffering and that “home” lies elsewhere, even within them: “Trees are better than stone — life commemorating life,” she says.

The Present

2004–2022

‘To Take Root Among the Stars’

‘To Take Root Among the Stars’

A barren landscape that becomes obscured in a cloud of points, before dispersing as the point of view pans through the legs of the Perseverance Rover on the terrain of Mars.

In “Parable of the Sower,” Butler describes Mars — which becomes a refuge for people escaping a dying Earth — as “cold, empty, almost airless, dead. Yet it’s heaven in a way.”

In 2021, NASA gave a name to the Mars landing site for the Perseverance rover: the Octavia E. Butler Landing.

“The fact that her works are as relevant today — if not more so — than when they were originally written and published is a testament to her vision, genius and timelessness,” said Kathryn Stack Morgan, a scientist on the Perseverance project.

In 2004, at Black to the Future, a science fiction festival in Seattle, Butler stood before an enthusiastic gathering of Black cross-disciplinary artists and spoke about her early years attempting to connect with other Black science fiction enthusiasts. At her first convention in 1970, she said, there was only one other Black person there.

As years passed, she would survey convention crowds and count a few more faces, but “I was either the only Black person or one of two or three,” she said.

She would interact with Black audiences at academic conferences: writers and library groups who read “SF” — her term of choice — for fun. Still, she recalled, “even people who said they would like to write it … they didn’t think we did that. Well, back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, we pretty much didn’t do that.”

More than “topics” or “themes,” Butler confronted pressing concerns and vexations humans found themselves in — the violence and suffering they inflicted on others and often on themselves. As a writer, Butler wasn’t interested in checking boxes. She was looking past what we could see, gathering the questions and casting about for the necessary tools that might help to create a better future — to encourage people to be critical thinkers and active agents in their own destinies.

She often had to defend her choices. She was persistently asked, “What good is science fiction to Black people?”

To which she would typically reply: “What good is any form of literature to Black people? What good is thinking about the future, warning, pointing the way? What good is examining the possible effects of science or social organization or political movements?”

Fiction was more than “stories,” she felt. It was a way to acquire a new set of eyes — to effect change.

She’d seen it in her own life.

“Octavia destroyed the sources of her own comfort without hesitation,” Nisi Shawl, an author and student of Butler’s, wrote in the introduction to the 2021 Library of America edition of Butler’s collected works. What Butler passed down to the following generations of writers, Shawl said, is the permission to do the same. “Strong emotions, she counseled me, are the best basis for stories,” Shawl wrote. “What do you fear? What do you loathe? What would you give anything to rescue and protect and preserve for eternity? Write about that.”

Butler’s effect was indelible: Just being in the room, on a stage, behind a lectern, her very presence forced this consideration, pushing a more inclusive conversation. Her point of view was one not traditionally found in science fiction and, simply by writing, she demanded a larger world.

Like the pomegranate trees whose life cycles she once studied in her native Pasadena, her vision has proved enduring and fruitful. She is remembered as serious and funny, relentless and disciplined, in her novels and her personal journals. For someone who only lived to 58, she gave so much, in her work and in her life — sowing seeds.

When asked once where she felt her place was in the world, Butler replied, “I think my place is wherever I happen to be standing.”

She wasn’t interested in writing “heroes.” She was interested in finding ways that imperfect humans might learn to secure a future beyond what they see.

While scrolling down, the point of view also pans down, moving from the tops of the leaves of a pomegranate tree to the base of its trunk and the surrounding flowers and plants on the ground.

“I don’t write about heroes,” Butler once said. “I write about people who survive and sometimes prevail.”

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/11/17/arts/octavia-butler-vision-kindred.html Octavia Butler’s Science Fiction Predicted the World We Live In