California tops FEMA’s new list of areas vulnerable to weather disasters. What does it mean for the Bay Area?

Despite the name, “Community Disaster Resilience Zones” are not local havens capable of withstanding storms and other extreme weather. But the Federal Emergency Management Agency, better known as FEMA, is spending billions in hopes that they can be.

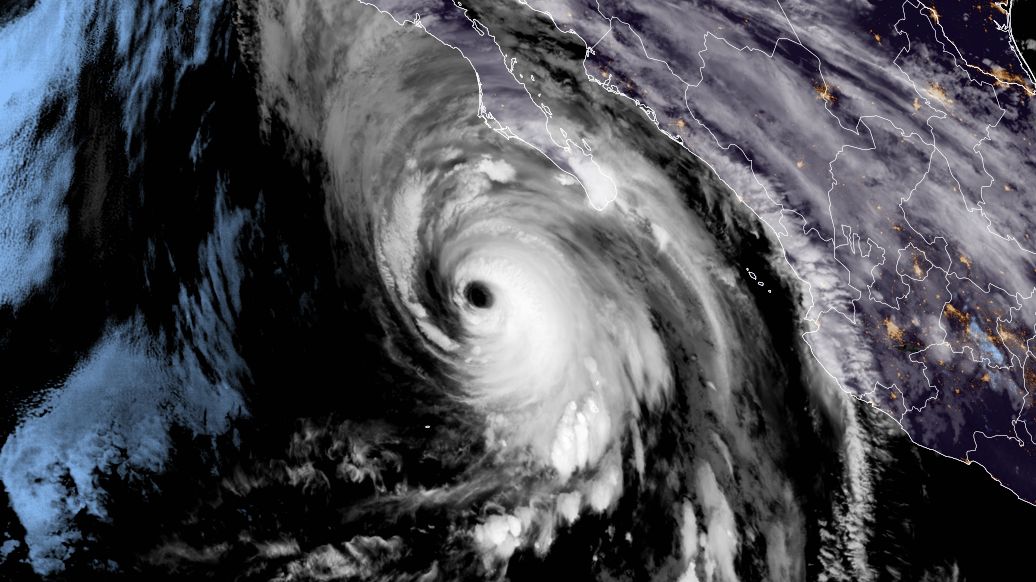

The agency has identified nearly 500 such “zones,” swaths of land generally covering several miles that are ill-prepared to tolerate flooding, earthquakes, heat waves, wildfires, landslides and other natural hazards. As extreme weather is expected to continue shattering expectations and local records — from downpours drenching Death Valley to hurricanes pummeling California’s coastline — these areas will be prioritized for additional funding for protective improvements.

While the new zones aren’t promised any specific funding, projects in selected census tracts will be prioritized for annual resilience grant programs and an increased federal cost share from FEMA other federal agencies — tapping budgets that President Joe Biden’s administration increased from $700 million to nearly $3 billion in August.

San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan said the increased pre-disaster planning will help mitigate damage in vulnerable areas of the country — 500 census tracts at a time.

“Preparing for a disaster before it occurs is the best way to save lives and money in the long run,” Mahan said in a statement. “It’s also a matter of equity. Historically vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected by natural disasters, and these dollars will help us protect our wonderfully diverse San Jose community.”

California topped all states in FEMA’s new plan, with 51 total zones — including seven census tracts in the Bay Area — followed by 35 in Texas and 32 in Florida.

Locally, these local Community Disaster Resilience Zones are primarily concentrated near waterways prone to flooding and earthquakes across Alameda and Santa Clara counties — as well as one that includes much of San Francisco’s Union Square and surrounding areas. Each scored in the 99th percentile of FEMA’s National Risk Index, beating out roughly 84,000 other tracts across the nation.

It’s not news that Coyote Creek in San Jose, tidelands abutting Fremont’s Tesla Factory and Bay Farm Island near Alameda, Oakland and San Leandro’s city limits are often swept up in storm coverage headlines, most recently during a gantlet of high-powered January storms that soaked the state.

But the hope is to increase resilience proactively rather than rely on reactive requests for aid after the damage is done. Climate researchers estimated that there were 122 billion-dollar disasters across the U.S. between 2016 and 2022, surpassing $1 trillion in losses and 5,000 deaths. And those events are only increasing in frequency.

San Jose’s tract 503122 — one of the seven Bay Area disaster resilience zones — faced one of the worst local calamities in recent memory. In 2017, torrential atmospheric rivers overflowed Coyote Creek’s banks, submerging more than 200 people’s homes and belongings between Happy Hollow Zoo and Highway 101 north of Japantown.

That flooding caused an estimated $100 million in damage and forced 14,000 people to evacuate, hundreds of whom collectively sued Silicon Valley’s largest water agency for $8.25 million and settled with the city of San Jose for $700,000 to compensate personal losses.

The hope is that philanthropies and private companies will jump on the bandwagon and also help fund projects in Community Disaster Resilience Zones, which were created by a 2022 federal bill, and help propel local governments’ own disaster-preparedness plans — which range from retrofitting vulnerable buildings and installing floodwalls to building horizontal levees and restoring native eelgrass beds.

This work is well underway across the Bay. Some efforts, such as the Bay Farm Island Adaptation Project, led by the collaborative San Leandro Bay/Oakland-Alameda Estuary Adaptation Working Group, have already obtained millions from FEMA’s Pre-Disaster Mitigation grant program.

But Danielle Mieler, the city of Alameda’s sustainability and resilience manager, hopes that these new zones will make it even easier to finance projects that can tackle several community goals at once, especially near lower income neighborhoods that have lacked investment for a long time.

These projects “have been really forward thinking and out of the box about how this region could be transformed in the future, because we don’t want to just protect against sea level rise,” Mieler said. “We want to make sure that we’re moving forward in a positive way — restoring habitats, protecting communities and providing recreational access so that this is a place that everyone can continue to live and work for the long term.”

Michael McCormick, director of the Bay Area Climate Adaptation Network (BayCAN) and president of climate change consulting firm Farallon Strategies, said in an interview that he was also encouraged by these community resilience zones, which were created using newer data that wasn’t available before the Biden administration took office.

He lauded this type of pre-disaster mitigation approach — even in its early stages — as a way for the federal government to assist local officials creatively and holistically solve problems before the need is dire, alongside mandates since 2015 for local governments to include adaptation within their general plans.

“There are so many more communities in the Bay Area that should have a higher priority, but we understand FEMA can’t just push money out to everybody all at once,” McCormick said. “What I feel like FEMA is trying to do here is push resources faster, more efficientl, and in more creative ways — it’s really refreshing to see. Obviously every community would love to be on that list, but it’s a good start.”

Especially as the rate of billion-dollar disasters is steadily increasing and private insurers are bailing out of risky areas, he said resiliency work can help FEMA and the Bay Area get ahead now and avoid footing an even higher bill down the line.

“You don’t want to be in an urgent recovery mode — when people don’t have access to their homes, buildings or businesses — and try to do something creative,” McCormick said. “We can make so much more progress on community resilience in a very short amount of time if we change the way we do things. We just don’t have the resources in our communities that can handle repetitive disasters that are facing them every year.”

https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2023/09/19/california-tops-femas-new-list-of-areas-vulnerable-to-weather-disasters-what-does-it-mean-for-the-bay-area/ California tops FEMA’s new list of areas vulnerable to weather disasters. What does it mean for the Bay Area?