All Chips — But British Manufacturers Are Short

Back in the 1980s, when leading British chip architect Arm was called Acorn Computers, a car might have had three chips. Today there are over 2,000 of them, and the auto industry stalled when semiconductor supplies ran out during the pandemic.

Even as the economy slows and the banks are in crisis, the demand for ever-smaller, ever-more powerful microchips knows no bounds. “Chips are more important than oil,” says Ian Lankshear, chief executive of chip designer EnSilica, quoted by Aim.

Consultant McKinsey predicts chip sales will reach $1 trillion by 2030. This is driven by his three sectors of automotive, computing and data storage, and wireless.

Even eight years ago, when Arm was valued at around £15 billion, Simon Segers, Arm’s then-CEO, said:internet of things”, demand for smart toasters and even smartphones. But I believed in Arm’s strategy of charging customers royalties and license fees for must-have processor designs.

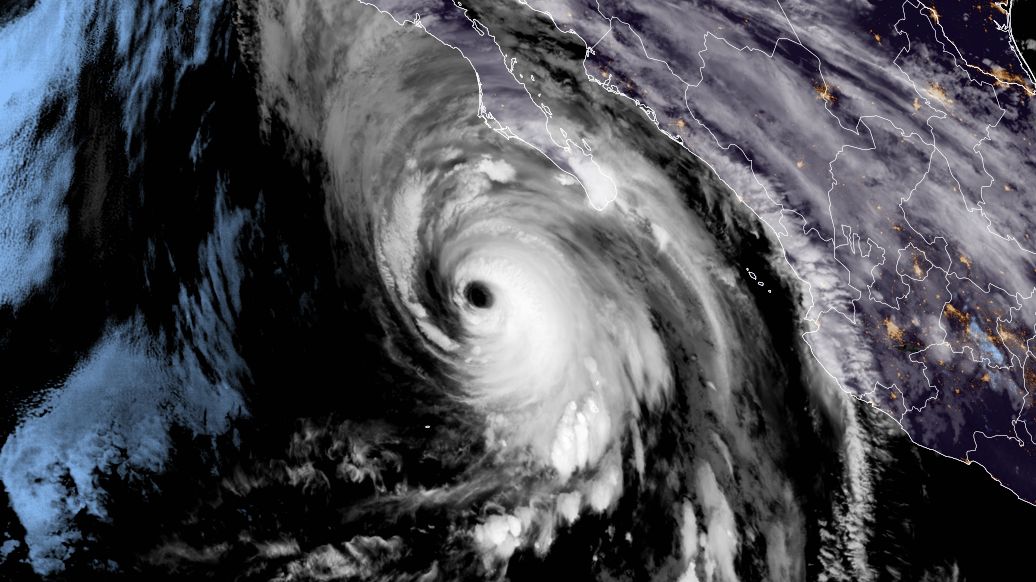

Now politicians lament that the UK will lose its only major success in the semiconductor industry. Relisted in the US at a value of $40 billion. They worry that the UK will forever be squeezed between US device makers and Asian manufacturing giants, relying on a key strategic component of a global chain at the mercy of geopolitics and geoeconomics. increase. Joe Biden recently funded US semiconductor manufacturing with $39 billion, and through the Chip and Science Act he provided $24 billion worth of manufacturing tax credits.

Still, according to a Policy Exchange report by Geoffrey Owen (former FT editor), the UK is building niche strengths and competitive advantages in the design of compound semiconductors for specialized applications such as defense and telecommunications. I came.

This made us wonder if an acorn-sized chip designer was lurking unnoticed in the UK market.

Not many, gloomily said Bob Liao, an analyst at broker Zeus Capital. The UK will always be at war with foreign companies backed by a spoiled government and deep-pocketed financiers.

Graham Curren, chief executive of Sondrel, a designer of application-specific integrated circuits (ASICS), agrees that UK tech start-ups are in a tough spot.organized rescue UK Division of Silicon Valley Bank It only highlights a funding gap for tech aspirants in the UK.

The problem is that UK investors focus too much on return on capital, become suspicious of cash-hungry companies competing for a foothold in a competitive industry, and sell out too quickly, tech entrepreneurs complain. there is

Readers may recall Dialog Semiconductor. flogging to Japanese rival Year 2021. Wolfson Microelectronics was acquired by a US competitor for around £300m in 2014. That same year, Qualcomm acquired Cambridge Silicon Radio for his $2.4 billion.

And then there was Imagination Technologies, once one of the UK’s largest listed technology companies, which went bankrupt when Apple stopped buying IP. Sold to venture capitalists for around £550m in 2017.

Investors will all too often argue that chip designers struggle to rack up revenue from partnerships and complicated multi-year license and service agreements.

Toronto chip creator Arm-wannabe Alphawave IP, which went public in London at 410 pence in 2021, Stock not recovered FT Alphaville questioned related-party-linked sales. Its share is about 120 pence.

Cardiff-based IQE, which manufactures wafers for fiber optic sensors, is constantly being hit by volatile earnings and multiple cash calls. At 25.85 pence, the stock is well off its 2018 high of 170 pence.

That said, Sondrel and EnSilica, 20-year-old semiconductor veterans who made their junior market debuts in the past year, are intriguing.

Based in Berkshire, Sondrel works with clients in futuristic areas such as self-driving cars and artificial intelligence. Lost money during the pandemic and now wants to oversee production of semiconductor designs. Growth is limited by headcount, Curren says.

By going to the manufacturing stage of the chip, the skill of the engineer can be leveraged and the bottom line can be increased at a small additional cost. The client will spend up to $30 million on the design and perhaps he will spend $100 million to produce it.

EnSilica, like Sondrel, is an Asic designer of chips that mix digital and analog signals for use in automobiles, broadband satellite communications, insulin pumps and heart monitors.

Lankshear and Curren both see opportunities in helping customers in Europe and the US manage their supply chains and bring production closer to home.

Broker Allenby Capital expects EnSilica to make a pre-tax profit of £500,000 by 2024 on sales of around £23m, compared to £15m in 2022.

Broker Cenkos believes Sondrel will generate around £40m in revenue, up from £17.5m in 2022, with a pre-tax profit of £2.4m in 2024. Turnover he could double again by 2025.

I don’t take challenges lightly. One of her biggest challenges is recruiting. Chip engineers are in short supply, and both Sondrel and EnSilica have gone to great lengths to secure the missing skills.

Also remember CML Microsystems. Another mixed-signal chip designer recently switched to Aim after years of struggling in major markets.

We have cash and we pay dividends, but in 2022 we only have £17m in sales and an adjusted profit before tax of £2m. The company’s share price, worth nearly £90m, has just returned to 2000 levels.

I admit that investing in small chip companies is a leap of faith. Orcs do grow from acorns, but they grow slowly and nothing grows as powerfully as arms.

https://www.ft.com/content/65a1eb8b-910a-4cd7-90cc-46f067bd0333 All Chips — But British Manufacturers Are Short